Bitcoin is really cool. Sure, there's arguments to be made about whether it's a useful technology, whether we're currently in a cryptocurrency bubble or if the governance problems that it's currently facing will ever be resolved.. But on a purely technical level, the mystical Satoshi Nakamoto created an impressive technology.

Unfortunately, while there's a lot of resources out there that give high level explanations of how Bitcoin works (one such resource I'd highly recommend is Anders Brownworth's fantastic blockchain visual 101 video), there isn't a whole heap of information at a lower level and, in my opinion, there's only so much you can properly grok if you're looking at the 10000 ft view.

As someone relatively new to the space, I found myself hungry to understand the mechanics of how Bitcoin works. Luckily, because Bitcoin is decentralised and peer to peer by its nature, anyone is able to develop a client that conforms to the protocol. In order to get a greater appreciation of how Bitcoin works, I decided to write my own small toy Bitcoin client that was able to publish a transaction to the Bitcoin blockchain.

This post walks through the process of creating a minimally viable Bitcoin client that can create a transaction and submit it to the Bitcoin peer to peer network so that it is included in the Blockchain. If you'd rather just read the raw code, feel free to check out my Github repo.

Address generation

In order to be part of the Bitcoin network, it's necessary to have an address from which you can send and receive funds. Bitcoin uses public key cryptography and an address is basically a hashed version of a public key that has been derived from a secret private key. Surprisingly, and unlike most public key cryptography, the public key is also kept secret until funds are sent from the address - but more on that later.

A quick aside on terminology: In Bitcoin, the term "wallet" is used by clients to mean a collection of addresses. There's no concept of wallets at a protocol level, only addresses.

Bitcoin uses elliptic curve public-key cryptography for its addresses. At an ultra high level, elliptic curve cryptography is used to generate a public key from a private key, in the same way RSA would but with a lower footprint. If you're interested in learning a bit about the mathematics behind how this works, Cloudflare's primer is a fantastic resource.

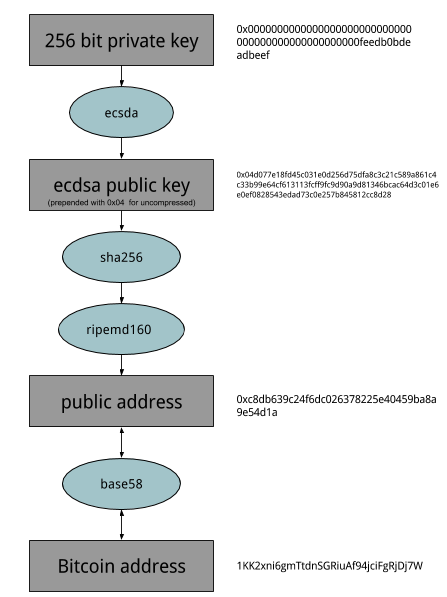

Starting with a 256 bit private key, the process of generating a Bitcoin address is shown below:

In Python, I use the ecsda library to do the heavy lifting for the elliptic curve cryptography. The following snippet gets a public key for the highly memorable (and highly insecure) private key 0xFEEDB0BDEADBEEF (front padded with enough zeros to make it 64 hex chars long, or 256 bits). You'd want a more secure method of generating private keys than this if you wanted to store any real value in an address!

As an amusing aside, I originally created an address using the private key 0xFACEBEEF and sent it 0.0005 BTC.. 1 month later and someone had stolen my 0.0005 BTC! I guess people must occasionally trawl through addresses with simple/common private keys. You really should use proper key derivation techniques!

from ecdsa import SECP256k1, SigningKey

def get_private_key(hex_string):

return bytes.fromhex(hex_string.zfill(64)) # pad the hex string to the required 64 characters

def get_public_key(private_key):

# this returns the concatenated x and y coordinates for the supplied private address

# the prepended 04 is used to signify that it's uncompressed

return (bytes.fromhex("04") + SigningKey.from_string(private_key, curve=SECP256k1).verifying_key.to_string())

private_key = get_private_key("FEEDB0BDEADBEEF")

public_key = get_public_key(private_key)

Running this code gets the private key (in hex) of

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000feedb0bdeadbeef

And the public key (in hex) of

04d077e18fd45c031e0d256d75dfa8c3c21c589a861c4c33b99e64cf613113fcff9fc9d90a9d81346bcac64d3c01e6e0ef0828543edad73c0e257b845812cc8d28

The 0x04 that prepends the public key signifies that this is an uncompressed public key, meaning that the x and y coordinates from the ECDSA are simply concatenated. Because of the way ECSDA works, if you know the x value, the y value can only take two values, one even and one odd. Using this information, it is possible to express a public key using x and the polarity of y. This reduces the public key size from 65 bits to 33 bits and the key (and subsequent computed address) are referred to as compressed. For compressed public keys, the prepended value will be 0x02 or 0x03 depending on the polarity of y. Uncompressed public keys are most commonly used in Bitcoin, so that's what I'll use here too.

From here, to generate the Bitcoin address from the public key, the public key is sha256 hashed and then ripemd160 hashed. This double hashing provides an extra layer of security and a ripemd160 hash provides a 160 bit hash of sha256's 256 bit hash, shortening the length of the address. An interesting result of this is that it is possible for two different public keys to hash to the same address! However, with 2^160 different addresses, this isn't likely to happen any time soon.

import hashlib

def get_public_address(public_key):

address = hashlib.sha256(public_key).digest()

h = hashlib.new('ripemd160')

h.update(address)

address = h.digest()

return address

public_address = get_public_address(public_key)

The code above generates a public address of c8db639c24f6dc026378225e40459ba8a9e54d1a. This is sometimes referred to as the hash 160 address.

As alluded to before, an interesting point is that both the conversion from private key to public key and the conversion from public key to public address are one way conversions. If you have an address, the only way to work backwards to find the associated public key is to solve a SHA256 hash. This is a little different to most public key cryptography, where your public key is published and your private key hidden. In this case, both public and private keys are hidden and the address (hashed public key) is published.

Public keys are hidden for good reason. Although it is normally infeasible to compute a private key from the corresponding public key, if the method of generating private keys has been compromised then having access to the public key makes it a lot easier to deduce the private key. In 2013, this infamously occurred for Android Bitcoin wallets. Android had a critical weakness generating random numbers, which opened a vector for attackers to find private keys from public keys. This is also why address reuse in Bitcoin is discouraged - to sign a transaction, you need to reveal your public key. If you don't reuse an address after sending a transaction from the address, you don't need worry about the public key of that address being exposed.

That standard way of expressing a Bitcoin address is to use the Base58Check encoding of it. This encoding is only a representation of an address (and so can be decoded/reversed). Base58Check generates addresses of the form 1661HxZpSy5jhcJ2k6av2dxuspa8aafDac. The Base58Check encoding provides a shorter address to express and also has an inbuilt checksum, that allows detection of mistyped address. In just about every Bitcoin client, the Base58Check encoding of your address is the address that you'll see. A Base58Check also includes a version number, which I'm setting to 0 in the code below - this represents that the address is a pubkey hash.

# 58 character alphabet used

BASE58_ALPHABET = '123456789ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijkmnopqrstuvwxyz'

def base58_encode(version, public_address):

"""

Gets a Base58Check string

See https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/base58Check_encoding

"""

version = bytes.fromhex(version)

checksum = hashlib.sha256(hashlib.sha256(version + public_address).digest()).digest()[:4]

payload = version + public_address + checksum

result = int.from_bytes(payload, byteorder="big")

print(result)

# count the leading 0s

padding = len(payload) - len(payload.lstrip(b'\0'))

encoded = []

while result != 0:

result, remainder = divmod(result, 58)

encoded.append(BASE58_ALPHABET[remainder])

return padding*"1" + "".join(encoded)[::-1]

bitcoin_address = base58_encode("00", public_address)

After all of that, starting with my private key of feedb0bdeadbeef (front padded with zeros), I've arrived with a Bitcoin address of 1KK2xni6gmTtdnSGRiuAf94jciFgRjDj7W!

With an address, it's now possible to get some Bitcoin! To get some Bitcoin into my address, I bought 0.0045 BTC (at the time of writing, around $11 USD) from btcmarkets using Australian dollars. Using btcmarket's trading portal, I transferred it to the above address, losing 0.0005 BTC to transaction fees in the process. You can see this transaction on the blockchain in transaction 95855ba9f46c6936d7b5ee6733c81e715ac92199938ce30ac3e1214b8c2cd8d7.

Connecting to the p2p network

Now that I have an address with some Bitcoin in it, things get more interesting. If I want to send that Bitcoin somewhere else, it's necessary to connect to the Bitcoin peer to peer network.

Bootstrapping

One of the sticking points I had when first learning about Bitcoin was, given the decentralised nature of the network, how do peers of the network find other peers? Without a centralised authority, how does a Bitcoin client know how to bootstrap and start talking to the rest of the network?

As it turns out, idealism submits to practicality and there is the slightest amount of centralisation in the initial peer discovery process. The principle way for a new client to find peers to connect to is to use a DNS lookup to any number of "DNS seed" servers that are maintained by members of the Bitcoin community.

It turns out DNS is well suited to this purpose of bootstrapping clients as the DNS protocol, which runs over UDP and is lightweight, is hard to DDoS. IRC was used as a previous bootstrapping method but was discontinued due to its weakness to DDoS attacks.

The seeds are hardcoded into Bitcoin core's source code but are subject to change by the core developers.

The Python code below connects to a DNS seed and arbitrarily chooses the first peer to connect to. Using the socket library, the code basically performs a nslookup and returns the ipv4 address of the first result on running a query against the seed node seed.bitcoin.sipa.be.

import socket

# use a dns request to a seed bitcoin DNS server to find a node

nodes = socket.getaddrinfo("seed.bitcoin.sipa.be", None)

# arbitrarily choose the first node

node = nodes[0][4][0]

After running this, the address returned was 208.67.251.126 which is a friendly peer that I can connect to!

Saying hi to my new peer friend

Bitcoin connections between peers are through TCP. Upon connecting to a peer, the beginning handshake message of the Bitcoin protocol is a Version message. Until peers swap Version messages, no other messages will be accepted.

Bitcoin protocol messages are well documented in the Bitcoin developer reference. Using the developer reference as guide, the version message can be constructed in Python as the snippet below shows. Most of the data is fairly uninteresting, administrative data which is used to establish the peer connection. If you're interested in more details than the attached comments provide, have a read of the developer reference.

version = 70014

services = 1 # not a full node, cant provide any data

timestamp = int(time.time())

addr_recvservices = 1

addr_recvipaddress = socket.inet_pton(socket.AF_INET6, "::ffff:127.0.0.1") #ip address of receiving node in big endian

addr_recvport = 8333

addr_transservices = 1

addr_transipaddress = socket.inet_pton(socket.AF_INET6, "::ffff:127.0.0.1")

addr_transport = 8333

nonce = 0

user_agentbytes = 0

start_height = 329167

relay = 0

Using Python's struct library the version payload data is packed into the right format, paying special attention to endianness and byte widths of the data. Packing the data into the right format is important, or else the receiving peer won't be able to understand the raw bytes that it receives.

payload = struct.pack("<I", version)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", services)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", timestamp)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", addr_recvservices)

payload += struct.pack("16s", addr_recvipaddress)

payload += struct.pack(">H", addr_recvport)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", addr_transservices)

payload += struct.pack("16s", addr_transipaddress)

payload += struct.pack(">H", addr_transport)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", nonce)

payload += struct.pack("<H", user_agentbytes)

payload += struct.pack("<I", start_height)

Again, the way in which this data should be packed is available in the developer reference. Finally, each payload transmitted on the Bitcoin network needs to be prepended with a header, that contains the length of the payload, a checksum and the type of message the payload is. The header also contains the magic constant 0xF9BEB4D9 which is set for all mainnet Bitcoin messages. The following function gets a Bitcoin message with header attached.

def get_bitcoin_message(message_type, payload):

header = struct.pack(">L", 0xF9BEB4D9)

header += struct.pack("12s", bytes(message_type, 'utf-8'))

header += struct.pack("<L", len(payload))

header += hashlib.sha256(hashlib.sha256(payload).digest()).digest()[:4]

return header + payload

With the data packed into the right format, and the header attached, it can be sent off to our peer!

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((node, 8333))

s.send(get_bitcoin_message("version", payload))

print(s.recv(1024))

The Bitcoin protocol mandates that on receiving a version message, a peer should respond with a Verack acknowledgement message. Because I'm building a tiny "for fun" client, and because peers won't treat me differently if I don't, I'll disregard their version message and not send them the acknowledgement. Sending the Version message as I connect is enough to allow me to later send more meaningful messages.

Running the above snippet prints out the following. It certainly looks promising - "Satoshi" and "Verack" are good words to see in the dump out! If my version message had been malformed, the peer would not have responded at all.

b'\xf9\xbe\xb4\xd9version\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00f\x00\x00\x00\xf8\xdd\x9aL\x7f\x11\x01\x00\r\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xddR1Y\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xff\xff\xcb\xce\x1d\xfc\xe9j\r\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x06\xb8>*\x88@I\x8e\x10/Satoshi:0.14.0/t)\x07\x00\x01\xf9\xbe\xb4\xd9verack\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00]\xf6\xe0\xe2'

Bitcoin transactions

To transfer Bitcoin it's necessary to broadcast a transaction to the Bitcoin network.

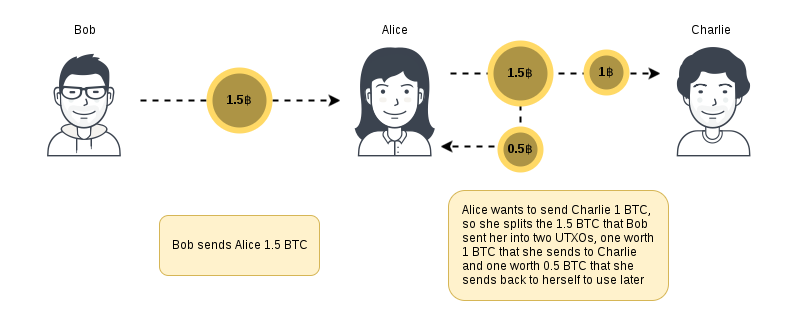

Critically, the most important idea to understand is that the balance of a Bitcoin address is comprised solely by the number of "Unspent Transaction Outputs" (UTXO) that the address can spend. When Bob sends a Bitcoin to Alice, he's really just creating a UTXO that Alice (and only Alice) can later use to create another UTXO and send that Bitcoin on. The balance of a Bitcoin address is therefore defined by the amount of Bitcoin it is able to transfer to another address, rather than the amount of Bitcoin it has.

To emphasize, when someone says that they have X bitcoin, they're really saying that all of the UTXOs that they can spend sum to X bitcoin of value. The distinction is subtle but important, the balance of a Bitcoin address isn't recorded anywhere directly but rather can be found by summing the UTXOs that it can spend. When I came to this realisation it was definitely a "oh, that's how it works!" moment.

A side effect of this is that transaction outputs can either be unspent (UTXO) or completely spent. It isn't possible to only spend half of an output that someone has spent to you and then spend the rest at a later time. If you do want to spend a fraction of an output that you've received, you instead can send the fraction that you want to send while sending the rest back to yourself. A simplified version of this is shown in the diagram below.

When a transaction output is created, it is created with a locking condition that will allow someone in the future to spend it, through what are called transaction scripts. Most commonly, this locking condition is: "to spend this output, you need to prove that you own the private key corresponding to a particular public address". This is called a "Pay-to-Public-Key-Hash" script. However, through Bitcoin script other types of conditions are possible. For example, an output could created that could be spent by anyone that could solve a certain hash or a transaction could be created that anyone could spend.

Through Script, it's possible to create simple contract based transactions. Script is a basic stack based language with number of operations centred around checking equality of hashes and verifying signatures. Script is not Turing complete and does not have the ability to have any loops. The competing cryptocurrency Ethereum built on this to be able to have "smart contracts", which does have a Turing complete language. There's much debate about the utility, necessity and security of including a Turing complete language in cryptocurrencies but I'll leave that debate to others!

In standard terminology, a Bitcoin transaction is made up of inputs and outputs. An input is a UTXO (that is now being spent) and an output is a new UTXO. There can be multiple outputs for a single input but an input needs to be completely spent in a transaction. Any part of an input leftover is claimed by miners as a mining fee.

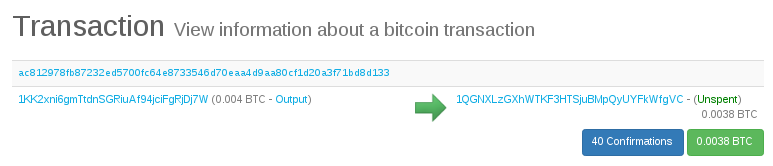

For my toy client I want to be able to send on the Bitcoin previously transferred from an exchange to my FEEDB0BDEADBEEF address. Using the same process as before, I generated another address using the private key (before padding of) BADCAFEFABC0FFEE. This generated the address 1QGNXLzGXhWTKF3HTSjuBMpQyUYFkWfgVC.

Creating a raw transaction

Creating a transaction is a matter of first packing a "raw transaction" and then signing the raw transaction. Again, the developer reference has a description of what goes into a transaction. What makes up a transaction is shown below but a few notes first:

-

Common Bitcoin parlance uses the terms signature script and pubkey script which I find a little confusing. The signature script is used to meet the conditions of the UTXO that we want to use in the transaction and the pubkey script is used to set the conditions that need to be met to spend the UTXO we are creating. A better name for the signature script might be a unlocking script and a better name for the pubkey script might be a locking script.

-

Bitcoin transaction values are specified in Satoshis. A Satoshi represents the smallest divisible part of a Bitcoin and represents one hundred millionth of a Bitcoin.

For simplicity, what is shown below is for a transaction for one output and one input. More complex transactions, with multiple inputs and outputs are possible to create in the same way.

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Version | Transaction version (currently always 1) |

| Number of inputs | Number of inputs to spend |

| Transaction ID | Transaction from which to spend |

| Output number | Output of the transaction to spend |

| Signature script length | Length in bytes of the sig script |

| Signature script | Signature script in the Script language |

| Sequence number | Always 0xffffffff unless you wish to use a lock time |

| Number of outputs | Number of outputs to create |

| Value | Number of Satoshis to spend |

| Pubkey script length | Length in bytes of the pubkey script |

| Pubkey script | Pubkey script in the Script language |

| Lock time | Earliest time/block number that this transaction can be included in a block |

Ignoring the signature script and pubkey script for now, it's quite easy to see what should go in the other fields of the raw transaction. To send the funds in my FEEDB0BDEADBEEF address to my BADCAFEFABC0FFEE address, I look at the transaction that was created by the exchange. This gives me:

- The transaction id is

95855ba9f46c6936d7b5ee6733c81e715ac92199938ce30ac3e1214b8c2cd8d7. - The output that was sent to my address was the second output, output

1(output numbers are 0 indexed). - Number of outputs is 1, as I want to send everything in

FEEDB0BDEADBEEFtoBADCAFEFABC0FFEE. - Value can be at most 400,000 Satoshis. It must be less than this to allow some fees. I'll allow 20,000 Satoshi to be taken as a fee so will set value to 380,000.

- Lock time will be set to 0, this allows the transaction to be included at any time or block.

For the Pubkey script of our transaction, we use a Pay to Pubkey hash (or p2pk) script. The script ensures that only the person that holds the public key that hashes to the provided Bitcoin address is able to spend the created output and that a supplied signature has been generated by the person that holds the corresponding private key to the public key.

To unlock a transaction that has been locked by a p2pk script, the user provides their public key and a signature of the hash of the raw transaction. The public key is hashed and compared to the address that the script was created with and the signature is verified for the supplied public key. If the hash of the public key and the address are equal, and the signature is verified, the output can be spent.

In Bitcoin script operands, the p2pk script looks as follows.

OP_DUP

OP_HASH160

<Length of address in bytes>

<Bitcoin address>

OP_EQUALVERIFY

OP_CHECKSIG

Converting the operands to their values (these can be found on the wiki) and inputting the public address (before it has been Base58Check encoded) gives the following script in hex:

0x76

0xA9

0x14

0xFF33195EC053D6E58D5FD3CC67747D3E1C71B280

0x88

0xAC

The address is found using the earlier shown code for deriving an address from a private key, for the private key we're sending to, 0xBADCAFEFABC0FFEE.

Signing the transaction

There are two separate, but somewhat related, uses for the signature script in a (p2pk) transaction:

- The script verifies (unlocks) the UTXO that we are are trying to spend, by providing our public key that hashes to the address that the UTXO has been sent

- The script also signs the transaction that we are submitting to the network, such that nobody is able to modify the transaction without invalidating the signature

However, the raw transaction contains the signature script which should contain a signature of the raw transaction! This chicken and egg problem is solved by placing the Pubkey script of the UTXO we're using in the signature script slot prior to signing the raw transaction. As far as I could tell, there doesn't seem to be any good reason for using the Pubkey as the placeholder, it could really be any arbitrary data.

Before the raw transaction is hashed, it also needs to have a Hashtype value appended. The most common hashtype value is SIGHASH_ALL, which signs the whole structure such that no inputs or outputs can be modified. The linked wiki page lists other hash types, which can allow combinations of inputs and outputs to be modified after the transaction has been signed.

The below functions put together a python dictionary of raw transaction values.

def get_p2pkh_script(pub_key):

"""

This is the standard 'pay to pubkey hash' script

"""

# OP_DUP then OP_HASH160 then 20 bytes (pub address length)

script = bytes.fromhex("76a914")

# The address to pay to

script += pub_key

# OP_EQUALVERIFY then OP_CHECKSIG

script += bytes.fromhex("88ac")

return script

def get_raw_transaction(from_addr, to_addr, transaction_hash, output_index, satoshis_spend):

"""

Gets a raw transaction for a one input to one output transaction

"""

transaction = {}

transaction["version"] = 1

transaction["num_inputs"] = 1

# transaction byte order should be reversed:

# https://bitcoin.org/en/developer-reference#hash-byte-order

transaction["transaction_hash"] = bytes.fromhex(transaction_hash)[::-1]

transaction["output_index"] = output_index

# temporarily make the signature script the old pubkey script

# this will later be replaced. I'm assuming here that the previous

# pubkey script was a p2pkh script here

transaction["sig_script_length"] = 25

transaction["sig_script"] = get_p2pkh_script(from_addr)

transaction["sequence"] = 0xffffffff

transaction["num_outputs"] = 1

transaction["satoshis"] = satoshis_spend

transaction["pubkey_length"] = 25

transaction["pubkey_script"] = get_p2pkh_script(to_addr)

transaction["lock_time"] = 0

transaction["hash_code_type"] = 1

return transaction

Calling the code with the following values creates the raw transaction that I'm interested in making.

private_key = address_utils.get_private_key("FEEDB0BDEADBEEF")

public_key = address_utils.get_public_key(private_key)

from_address = address_utils.get_public_address(public_key)

to_address = address_utils.get_public_address(address_utils.get_public_key(address_utils.get_private_key("BADCAFEFABC0FFEE")))

transaction_id = "95855ba9f46c6936d7b5ee6733c81e715ac92199938ce30ac3e1214b8c2cd8d7"

satoshis = 380000

output_index = 1

raw = get_raw_transaction(from_address, to_address, transaction_id, output_index, satoshis)

It might be confusing to see that I'm using a private key to generate the to_address. This is really only done for convenience and to show how the to_address is found. If you were making a transaction to someone else, you'd ask them for their public address and transfer to that, you wouldn't need to know their private key.

In order to be able to sign, and eventually transmit the transaction to the network, the raw transaction needs to be packed appropriately. This is implemented in the get_packed_transaction function which I won't replicate here, as it's essentially just more struct packing code. If you're interested you can find it in the bitcoin_transaction_utils.py Python file in my Github repo.

This allows me to define a function that will produce the signature script. Once the signature script is generated, it should replace the placeholder signature script.

def get_transaction_signature(transaction, private_key):

"""

Gets the sigscript of a raw transaction

private_key should be in bytes form

"""

packed_raw_transaction = get_packed_transaction(transaction)

hash = hashlib.sha256(hashlib.sha256(packed_raw_transaction).digest()).digest()

public_key = address_utils.get_public_key(private_key)

key = SigningKey.from_string(private_key, curve=SECP256k1)

signature = key.sign_digest(hash, sigencode=util.sigencode_der)

signature += bytes.fromhex("01") #hash code type

sigscript = struct.pack("<B", len(signature))

sigscript += signature

sigscript += struct.pack("<B", len(public_key))

sigscript += public_key

return sigscript

Essentially, the signature script is provided as an input to the pubkey script of the previous transaction I'm trying to use, so that I can prove I am allowed to spend the output that I'm now using as an input. The mechanics of how this works is shown below, which is taken from the Bitcoin wiki. Working from top to bottom, each row is a one iteration of the script. This is for a pay to pubkey hash pubkey script, which, as mentioned earlier is the most common script. It is also the script that both the transaction I'm creating and the transaction I'm redeeming use.

| Stack | Script | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Empty | signature publicKey OP_DUP OP_HASH160 pubKeyHash OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG |

The signature and publicKey from the signature script are combined with the pubkey script. |

| signature publicKey |

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 pubKeyHash OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG |

The signature and publicKey are added to the stack. |

| signature publicKey publicKey |

OP_HASH160 pubKeyHash OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG |

The top stack item is duplicated by OP_DUP |

| signature publicKey pubHashA |

pubKeyHash OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG |

Top stack item (publicKey) is hashed by OP_HASH160, pushing pubHashA to the stack. |

| signature publicKey pubHashA pubKeyHash |

OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG |

pubKeyHash added to stack. |

| signature publicKey |

OP_CHECKSIG | Equality is checked between pubHashA and pubKeyHash. Execution will halt if not equal. |

| True | The signature is checked to see if it is a valid signature of the hash of the transaction from the provided publicKey. |

This script will fail if the provided public key doesn't hash to the public key hash in the script or if the provided signature doesn't match the provided public key. This ensures that only the person that holds the private key for the address in the pubkey script is able to spend the output.

You can see that here is the first time I have needed to provide my public key anywhere. Up until this point, only my public address has been published. It's necessary to provide the public key here as it is allows verification of the signature that the transaction has been signed with.

Using the get_transaction_signature function, we can now sign and pack our transaction ready for transmission! This involves replacing the placeholder signature script with the real signature script and removing the hash_code_type from the transaction as shown below.

signature = get_transaction_signature(raw, private_key )

raw["sig_script_length"] = len(signature)

raw["sig_script"] = signature

del raw["hash_code_type"]

transaction = get_packed_transaction(raw)

Publishing the transaction

With the transaction packed and signed, it's a matter of telling the network about it. Using a few functions previously defined in this article in bitcoin_p2p_message_utils.py, the below piece of code puts the Bitcoin message header on the transmission and transmits it to a peer. As mentioned earlier, it's first necessary to send a version message to the peer so that it accepts subsequent messages.

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((get_bitcoin_peer(), 8333))

s.send(get_bitcoin_message("version", get_version_payload())

s.send(get_bitcoin_message("tx", transaction)

Sending the transaction was the most annoying part of getting this to work. If I submitted a transaction that was incorrectly structured or signed, the peer often just dropped the connection or, in a slightly better case, sent cryptic error messages back. One such (very annoying) error message was "S value is unnecessarily high" which was caused by signing the transaction hash using the ECSDA encoding method of sigencode_der. Despite the signature being valid, apparently Bitcoin miners don't like ECSDA signatures formatted in such a way that allows spam in the network. The solution was to use the sigencode_der_canonize function which takes care to format the signatures in the other format. A simple, but extraordinarily hard to debug, issue!

In any case, I eventually got it to work and was very excited when I saw that my transaction made its way into the blockchain!! It was a great feeling of accomplishment knowing that my small, dinky, hand crafted transaction will now forever be a part of Bitcoin's ledger.

When I submitted the transaction, my transaction fee was actually quite low compared to the median (I used the bitcoin fees website to check) and as such it took around 5 hours for a miner to decide to include it in a block. I checked this by looking at the number of confirmations the transaction had - this is a measure of how many blocks deep the block with the transaction is in. At the time of writing this was at 190 confirmations.. meaning that after the block my transaction is in, there's another 190 blocks. This can be pretty safely considered confirmed, as it would take an impressive attack on the network to rewrite 190 blocks to remove my transaction.

Conclusion

I hope you've gained some appreciation of how Bitcoin works through reading this article, I know I certainly did during the months it took me to put all of this together! While most of the information presented here isn't too practicably applicable - you'd normally just use a client that does it all for you - I think having a greater understanding of how things work gives you a better appreciation of what's happening under the covers and gives makes you a more confident user of the technology.

If you'd like to peruse the code, or play around further with the toy examples, please check out my associated Github repo. There's a lot of room to explore further in the Bitcoin world, I've only really looked at a very common use case of Bitcoin. There's certainly room out there to do cooler feats than just transferring value between two addresses! I also didn't touch how mining, the process of adding transactions to the blockchain, works.. which is another rabbit hole all together.

If you've read this far you might have realised that the 380000 Satoshi (or 0.0038 BTC) that I transferred into 1QGNXLzGXhWTKF3HTSjuBMpQyUYFkWfgVC can, with enough smarts, be taken by anyone.. as the private key for the address exists within this article. I'm very interested to see how long it takes to be transferred away and hope that whoever takes it has the decency to do so using some of the techniques I've detailed here! It'd be pretty lame if you just loaded the private key into a wallet app to take it, but I guess I can't stop you! At the time of writing this amount is worth about $10 USD, but if Bitcoin "goes to the moon" who knows how much it might be worth! (Edit: And it's gone now! Taken by 1KgoPFVDNcx7H2VY9bB2dxxP9yNM2Nar1N after a few hours of posting this article. Well played!)

And just in case you're looking for an address to send Bitcoin to when you're playing around with this stuff, or if you think this post was valuable enough to warrant a tip - my address of 18uKa5c9S84tkN1ktuG568CR23vmeU7F5H is happy to take any small donations! Alternatively, if you want to yell at me about getting anything wrong, I'd love to hear it.

Further resources

If you found this article interesting, some further resources to check out:

- Mastering Bitcoin is a book that explains the technical details of Bitcoins. I haven't read this completely, but on a skim it looks like it is a wealth of good information.

- Ken Sheriff's blog article is a great source of information that covers a lot of the same topics as this article that I unfortunately only found this when I was nearly finished writing this article. If you didn't understand anything in this article, reading Ken's excellent post would be a good place to start.

- Mentioned earlier, but Anders Brownworth's fantastic blockchain visual 101 video is an excellent top level view of how blockchain technologies work.

- Unless you're a masochist for pain, I'd also recommend not doing everything from scratch unless you're interested in doing so for learning purposes. The pycoin library is a Python Bitcoin library that will save you a few headaches.

- To also save yourself pain, it's probably advisable to use the Bitcoin testnet to play around with, rather than using the mainnet like I did. That said, it's more fun when the risk of your code being wrong is losing real money!

- Lastly, it is probably worth repeating that the accompanying code for this article can be found in my Github repo.